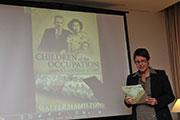

Children of the Occupation: Japan's Untold Story

Walter Hamilton, Journalist

25 October, 2012 at the Australian Embassy Tokyo

Good evening.

I wonder if any of you recognize this: a cathedral, maybe, or the wreckage of an alien spacecraft?

No. It is the remains of a grandstand that once overlooked a horse race track in the suburbs of Yokohama.

Since the end of the Second World War, the former racetrack land has been appropriated for a large US military facility.

I mention this because nearby there is an even older remnant of the past: Negishi Foreigners' Cemetery - in use since 1880, and which we visited this morning.

In this cemetery, alongside the diplomats and silk traders, you will find a monument to the unnamed dead also buried here, including, it is said, more than 800 infants abandoned during the occupation… whose fathers were foreign servicemen.

Those of you who follow NHK's morning drama 'Jun and Ai' perhaps will have noticed that - in common with other TV entertainments - 'hafu' actors are performing prominent roles. Many will also know that, in the present era of stagnant population growth, international marriages are on the rise in Japan. Being a 'hafu' has become smart and cute. But this wasn't always the case.

My topic tonight is a missing chapter in the history of the Australia-Japan relationship. I consider it a sign of the maturity of the relationship that I have been invited to give this talk tonight. For making the opportunity, I wish to thank our host Minister-Counsellor Ms Dara Williams and Embassy Cultural Officer Ms Hitomi Toku.

On Japan's surrender in 1945, Australia sought a major role in settling postwar arrangements in the Pacific. Though the United States continued to dominate Allied policy-making, Australia gained a direct hand in the enforcement of political and economic reforms, the punishment of war criminals, and the demilitarization of the defeated enemy. When the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) arrived in early-1946, an Australian general, Sir Horace Robertson, was in command.

BCOF brought nearly 40,000 troops from Britain, India, New Zealand and Australia. The force took over responsibility for nine prefectures in western Japan, making its headquarters in the bomb-scarred port city of Kure, Hiroshima prefecture. The Australians remained long after the other Commonwealth contingents left Japan. Indeed, troops were still stationed there ten years later.

BCOF maintained a policy of non-fraternisation. For instance, no soldier was ever given permission to marry a Japanese. Some defied the ban, and children were born; but if the soldier was found out, or his term of duty ended, he was forcibly separated from his family. Though the marriage ban was eventually lifted in 1952, clearing the way for hundreds of Japanese war brides to enter Australia, the policy change came too late for many others.

Allied military censors deleted references to the occupation children from Japanese magazines and newspapers. It was a taboo subject. One result, ironically, was that the public formed an exaggerated impression of the problem. It was widely reported that Japan had been lumbered with 200,000 mixed-bloods, and yet the real number was nearer 10,000. The appearance of 'black' Japanese caused most anxiety.

The US government responded to the controversy by opening its doors in 1953 to allow American families to adopt the children. More than 2,000 went to America by this route. The Australian government, however, opposed adoptions, on the grounds that 'half-castes' would not be able to assimilate.

The only child to slip through the net was this two-year-old boy. The Australian soldier who adopted him, and took him home, wanted to prove a point. Not only did Peter (Hideki) Budworth successfully assimilate - he went on to become a senior officer in the Australian Federal Police and was decorated by the Governor-General.

Facing public criticism for its hard line on adoption, in 1962 the Federal Cabinet began funding a welfare agency, International Social Service (ISS), to assist the most vulnerable children left behind in Kure. Private charitable donations were also sent from Australia.

For 17 years, the Kure Project provided counseling, financial aid, and educational scholarships to more than 100 children, about half of whom were identified as having Australian fathers. I should add, this was not the total number of Australia-fathered children left in Japan; I estimate that figure to be in the low hundreds.

Around 20-30 per cent of all fatherless occupation children were either adopted abroad, went abroad after finishing school, or spent time in an orphanage. The remainder were raised in the community and settled in Japan, battling discrimination mainly due to their low socio-economic status. But their lives were not universally unhappy or unproductive, contrary to first predictions.

Baby George's parents married secretly in 1949. He was born six months before his Australian father died while serving in the Korean War. George's mother, now destitute, left her baby with an elderly couple and disappeared. ISS came to the rescue, but so strong was society's ill feeling towards the children, it could not prevent the good-natured boy turning delinquent.

It was George's great good fortune that he married young and was blessed with three up-standing sons. Family responsibilities forced him to take stock of his life.

He recently retired after 40 years as a stevedore on the Nagoya docks. In the family shrine, he keeps a photograph of his father - acquired on a visit to Australia in 2007 - before which he prays each morning.

This is Kazumi Yoshida. Her mother, Mitsuko, was working as a waitress at a BCOF sergeant's mess in Kure when she met Kazumi's father. He departed for Australia before his daughter was born, in November 1947, and made no further contact.

Because she looked Japanese, Kazumi fared better at school than some other Kure Kids; a bigger problem for the family was lack of income. At one point, Kazumi had to talk her mother out of committing suicide so severe were the burdens of daily life.

Believing her daughter would be happier living abroad, Mitsuko accepted a marriage proposal from an Australian ex-serviceman and they left Japan in 1965.

Here is Kazumi (on the right) in Melbourne today, with her mother and one of her daughters.

Soon after this photo was taken, Kazumi achieved a lifetime's dream. With her daughter's help, she was able to trace her natural father. Though he had passed away by now, she discovered he was already married when he went to Japan, and there were four other children. Kazumi made herself known to her half-siblings and was embraced by her new family.

Such 'Cinderella' moments have been the exception. The girl in the picture was 18 when she became pregnant. The ordeal left her mentally scarred for life.

She gave birth to a daughter, Mayumi, who was adopted by the girl's aunt.

Mayumi grew up knowing nothing of her father, not even a name. Even so, she became a leader among the Kure Kids, and with help from ISS graduated from university and found a respectable place in society.

Masaaki's father remained on the scene until his son was six; some men simply could not face the prospect of taking home a Japanese wife. It was left up to the boy, instead, to prove himself 'a worthy Japanese'.

That became possible after he demonstrated an exceptional talent for running. Sport and entertainment were fields in which the occupation children could turn their physical difference to advantage.

Today Masaaki goes by the name of Johnny, and has been adopted into his wife's family. When he was in his twenties, he reaffirmed his Australian identity and succeeded in meeting his father again.

The couple run an English language school in Amakusa - sharing their time between Japan and Australia.

These are just a few of the people featured in my book, "Children of the Occupation: Japan's Untold Story". Not all, I might add, were as successful as these individuals; there are many aspects of this living history I have not had time to cover in this talk. Perhaps I can address some of them while answering your questions. Thank you for your attention.